UAM gets ready to take to the skies

14th Feb 2023 | In News | By Mike Richardson

According to Altair’s senior technical account manager, Blaise Cole urban air mobility is getting closer, but there is still plenty of work to do.

Even if you haven’t heard of urban air mobility (UAM), you’ve surely seen its principles around you – especially in pop culture. The concept of flying cars has been in the public imagination for so long that it predates The Jetsons. Helicopters routinely dart around skyscrapers to transport news teams, law enforcement, and medical and natural disaster crews in the world’s biggest cities. And most recently, drones have captured the public imagination by providing ever-increasing levels of aerial mobility and agility. UAM mostly concerns itself with these drones and their technology – as cool as it would be, it’s unlikely everyone will be flying their own personal helicopter anytime soon. But drones that are capable of transporting people and light cargo are anything but science fiction, and in fact, are already on the horizon.

UAM: the basics and state of the industry

So what is UAM, and what does it hope to achieve? According to the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), UAM “envisions a safe and efficient aviation transportation system that will use highly automated aircraft that will operate and transport passengers or cargo at lower altitudes within urban and suburban areas.” The goal is that UAM will democratise short-distance urban and suburban air travel the way commercial airlines democratised long-distance air travel back in the mid-1950s. Ideally, UAM will help both people and things travel quicker and more freely, and ease the traffic congestion so prevalent in many cities today.

But you’ll note that even the FAA’s definition is in the future tense. Drone technology, along with other technologies that will enable UAM – including battery technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and others – have made great strides in the past 10-15 years, but we still aren’t there yet. The industry and UAM-specific technology is still young, so much so that completing a few minutes’ flight with cargo (and landing successfully) is still a major accomplishment. In many ways, it feels like we are close, yet still far away with UAM. Let me dive deeper into what UAM still needs to overcome.

Today’s UAM hurdles

First, the technology needs to keep progressing. If we want true UAM – fully autonomous vehicles capable of communicating, interacting, and travelling without a hitch – it will require highly advanced AI and autopilot systems and a litany of real-time data that will help manufacturers and operators assess performance while vehicles are in the field. While plenty of firms are making steady progress, the technology simply isn’t ready yet. We also need other things, mainly smaller, lighter, and longer-lasting batteries – a desire for almost anyone in the business of electrification.

But ironically, I don’t believe the technology is UAM’s biggest hurdle. Given today’s tools and computing power, the pace of technological change moves breath-taking speeds, and I have faith the technical aspects will come with a little time and healthy persistence.

The hard work is in the basics – safety. In my view, UAM’s biggest hurdles lie in the safety certification process and the complexity and detail needed to design the regulatory and operational systems that will accompany UAM. Let’s start with certification. Like other transportation industries (airline, rail, maritime, and automotive), UAM will have to undergo an extensive, rigorous certification process to ensure vehicles are safe in both normal operation and in emergency situations. Vehicles must prioritise the safety of passengers, cargo, and the surrounding people and buildings – no matter the weather conditions, country/region, cargo composition, and a million other factors. This is a slow, tedious, and unglamorous process, and one of the most important.

The same concepts apply to designing the infrastructure that will sustain the UAM industry. Like any other form of aircraft, UAM vehicles will need to coordinate with local and federal aviation personnel daily to coordinate schedules, routes, delays, physical infrastructure, etc. Will UAM resemble modern airports that host many aircraft, or will passengers and cargo hail drones like a taxi or an Uber? As I mentioned, the AI and automation for autopiloted vehicles isn’t there yet, so I think we’ll be seeing human pilots with full or partial control for at least the next 5-10 years. How will people become certified to fly? Will there be different types of certifications by states, regions, countries, etc.? Will we need to make changes to building and architectural codes to accommodate UAM traffic? There are still countless questions on the table – and given the nature of the technology, it will take time to get things right.

Looking ahead

I’m optimistic when I can be, but I’m a realist at heart. To many futurists’ dismay, I think UAM could still need up to a decade to fully develop, and even longer to become the norm. The industry is moving forward, yes, and we are closer than we’ve ever been – but a lot of work remains and, as it so often seems with new technology, the last mile can often be the slowest and most difficult. But like I said, UAM is also no longer relegated to fiction or hyperbole – it’s real, and I believe it will get there.

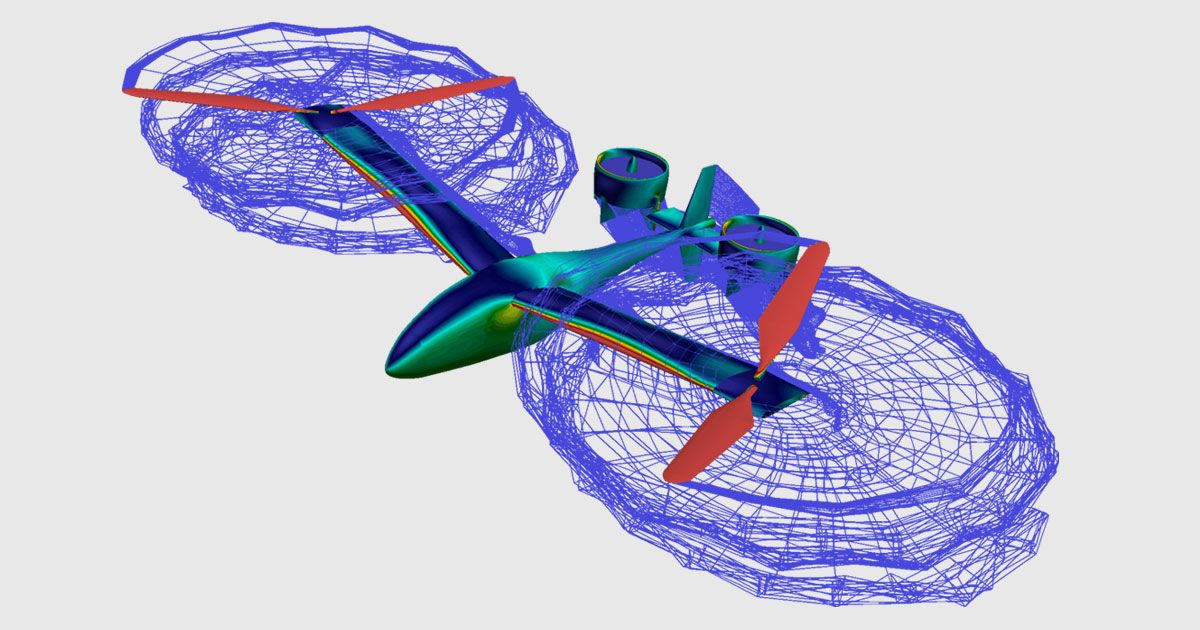

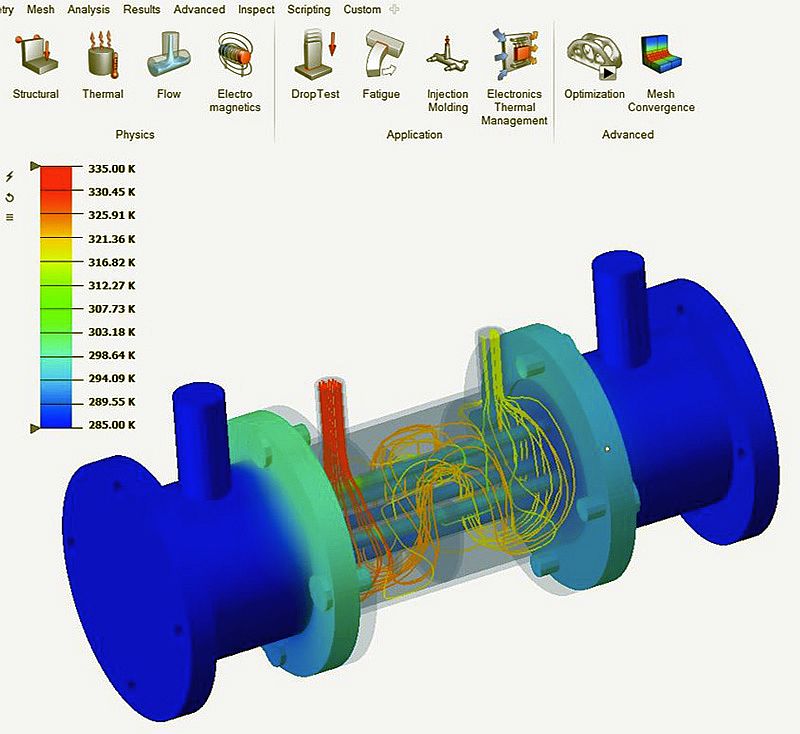

One of the main reasons I’m confident is because of today’s simulation and analytics tools, which aerospace organisations pioneered. Now, assisted by AI and machine learning, teams can simulate thousands of iterations, scenarios, variables, and prototypes faster and at higher fidelities than ever. Physical prototyping will always be around in the aerospace industry, but simulation helps companies design better vehicles the first time so they can be confident when they head into the field.

In the years to come, this technology will only expand, likely encompassing the entire simulation, data, and high-performance computing process and forming true digital twins. These digital twin workflows will open the floodgates for innovation and allow teams to gather real-time field data from active vehicles to iterate upon new designs and components, conduct predictive maintenance, and more.

Slowly but surely, UAM is getting there. The market is currently filled with lean, innovative startups who are already putting the pieces for full digital twin workflows into place – once they can invest the resources they need to build them, UAM will truly take to the skies.

Consider a free digital subscription

If you find this article informative, consider subscribing digitally to Aerospace Manufacturing for free. Keep up to date with the latest industry news in your inbox as well as being the first to receive our magazine in digital form.